In 1956 we moved from a two-bedroom apartment near First Avenue and 22nd Street in Manhattan to a converted barn in Pineville (population under 600). It was something about a more lenient tax structure for an artist in Pennsylvania. The barn was on two acres and only 65 miles from New York. My sister Kim was already five; the two of us had been sharing our bedroom with an enormous etching press. My father was the artist William A. Smith. The master bedroom doubled as Dad's studio. It was time for a bigger place.

I didn't want to move. I loved growing up in the city. I had lots of friends, loved the Yankees, and rock and roll was coming in. I wasn't sure they had that in Pennsylvania. It turned out, fortunately, to be very much alive out there and, best of all, Kim and I had our own rooms.

Mom and Dad had a huge bedroom overlooking onion grass and a row of tulips marching out to the Windy Bush Road, our new address. Dad's studio space was enough for easels, frame racks, posters, and the damn etching press. He was still within easy drive time of the art directors, costume rental warehouses, framers and photo studios he needed for his commissions from The Saturday Evening Post, Reader's Digest, and the various book publishers who kept him in work. Kim, Mom, neighbors and strangers could find themselves modeling for Dad and then recognizing themselves in a national magazine or on a book cover. Mom might be Catherine the Great one month and a barfly the next. I could be Abe Lincoln as a young boy one month and Hamlet the next. Kim is the little girl drawing on the pavement on page 33 of Carl Sandburg's Wind Song. That's her, too, arms around him on the back cover.

Those early April East Coast storms: the sky begins to brood, clouds move in fast and a light flurry drifts down, but it quickly becomes a dense sweeping deluge where visibility becomes nearly zero and silence envelops the landscape. It's beautiful, really, unless you're on the roads. It'll snow steadily for two, three, maybe four days until, finally, one morning, the sky will be blue and the sunlight reflecting off all that white will nearly blind you. There is a translucence to everything after those storms. The power lines, heavy with ice, droop and look like necklaces draped between the power poles. The tree branches look to be encased in Lucite, glassy and jewel-like; they start dripping once the sun hits them. When these storm fronts came in, we'd lose power, the pipes would freeze, and we'd boil snow for drinking water. The whole family would sleep on the floor in front of our river-rock fireplace. We'd have to use the shovel just to clear the five-foot drifts, to make a path to the firewood. We were stuck, sometimes for days. No school, roads closed and a one-mile trek to the Pineville General Store and post office up on Route 413, where snowplows and generators kept things going.

For years, Sandburg had been visiting our New York City apartment whenever he was in town from his home in Flat Rock, North Carolina. My sister Kim took her first steps into his arms back in 1952. And when we moved to Pennsylvania, he'd visit and Dad would often sketch him while they talked. Dad ended up doing a terrific pencil drawing of Sandburg's profile which appeared on the cover of Harvest Poems and also on an eight-cent U.S. postage stamp in the 1970s. Dad's photos and drawings graced the covers of several of Sandburg's books and record albums, but probably the best known of all Dad's work that came out of that relationship was the large oil portrait of Sandburg that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. He was, I think, the only artist to paint Sandburg from life.

Sandburg was in Pineville sitting for that portrait in early spring, 1959, when one of those storms hit Bucks County so hard that we were snowed in for four days. During that week, I slept in front of the fireplace and Sandburg took my bedroom. He told me one morning that he liked the books in my collection and that he had fallen asleep reading Greatest Moments in Baseball. He had to reach past William Blake, Joseph Campbell, Pearl Buck and Babe Pinelli to get that book. Born in Illinois, he was a ferocious Chicago baseball fan; he probably got wrapped up in tales of Stan Hack or Dizzy Dean. A Yankee fan, he was not. Being from Illinois, he was used to weather like this and worse. He settled in for the long haul. He and Dad were yin and yang. Sandburg spoke slowly and seemed calm and relaxed, almost meditative. Dad was antsy and unnerved by the delay. He was impatient and did a lot of sighing and pacing.

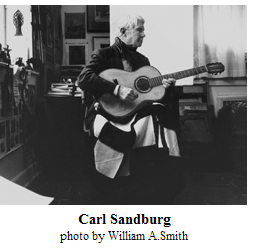

I don't know how much painting was accomplished that week. The windows were tall in Dad's studio and they let in northern light, but the light didn't last long. It was amazing how Mom was able to feed the house during those storms. Before Sandburg's arrival, she put in a stock of his favored goat's milk and, during the storm, she was able to appropriate some cod from a neighbor. The fireplace was built for northeast winters – deep and wide for cooking and for cutting the chill off those freezing nights. Mom's family was seventh generation Parisian; for Mom, cooking like a pioneer was a stretch, but she pulled it off. At night, after a candlelit dinner, Sandburg would pull out a guitar and sing. One of his many books was The American Songbag, an archival collection of folk songs from all sectors of our culture. He plowed through such classics as “C.C. Rider” and “Frankie and Johnny.” He was a strummer, really, but he knew the music and had a wonderful resonating tenor that also served him well at his book signings and poetry readings. A lot of the after-dinner music and conversation was taped on Dad's newfangled Tannhauser reel-to-reel deck. You can hear Sandburg singing and playing if you can find the studio recording, Carl Sandburg Sings His American Songbag. I've seen it online.

The conversations on the tapes were spirited, funny and intelligent. Sandburg and Dad had really become friends and kindred spirits. They both agreed that Stevenson and not Eisenhower should have become the 34th president; they both recognized McCarthyism for the threat to privacy and freedom of expression that it was. Sandburg was actively supportive of the working class as he made clear in such works as “Smoke and Steel” and “The People, Yes.” He was also an astute observer of character, recognizing and documenting my Dad's “galloping anxiety” in his poem “Bill Smith.” He was a poet for the everyman, a street poet more than an academic, and yet he firmly established his formidable scholarly skills in the exhaustive multi-volume biography of one of his heroes, Abraham Lincoln. He could work both sides of the literary street.

Sometimes, when you're a kid, you don't realize what's really going on until it's long over. I remember vividly my English teacher that year was Michael Casey. The day before the storm, I came into the studio after school waxing forth about newly learned poetry forms from Casey. Synecdoche, a tactic of implication, was one of them. Sandburg seemed impressed. In my history class, I was writing a paper about the Lincoln presidency. I challenged Sandburg with the question, “Who, in Lincoln's Cabinet, didn't wear a beard?” He turned it around on me with, “Are you asking about beards or just whiskers?” Now, when it dawns on me that Carl Sandburg got snowed in with us, slept in my bed, talked baseball with me, and led impromptu sing-alongs at our dinner table, I smile in wonder.

A Bucks County snow storm, frozen pumps, downed power lines, closed back roads and Sandburg's sweet tenor drifting across a candlelit room, still aglow in my memory of those long-ago winter nights.