My dad and my natural mom were just kids when they broke up; I was only four myself. It was the 1940s, a time when it was beyond rare for a father to gain custody of child in divorce court. My mother was battling an undiagnosed but debilitating endocrine condition which left her lethargic and disorganized; it seemed to take her away from herself. Years later, an observant physician did make the diagnosis and put her on a medication which turned her life around. Happily, by the time I was 18, she and I had established a loving and strong relationship. By then, I had a second mom.

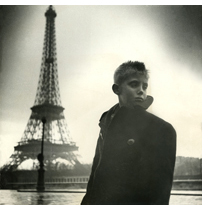

Dad married my new French mom in October of 1949. The modest ceremony at City Hall in Lower Manhattan was duly recorded; now they could share a cabin when we boarded the ocean liner, S.S. de Grasse, later that month and set out on the eight-day journey to the French port of Le Havre. There would be a cathedral wedding in Paris but, in the meantime, moral codes were intact. I had my own little cabin and a lot of free time on deck. I don't remember seeing either one of them much except at meals and at tea time. And sometimes they missed that. I do remember the Statue of Liberty receding into the distance and then the tug boats and sea gulls peeling off and heading back to shore. Being on the high seas was exciting and the time flew by. There was shuffle board, skeet shooting and wave watching. I explored the decks, the ladders to the bridge and the smokestack; I wandered around not really recognizing the inherent dangers of being too curious and too close to the rail. But, to look in all directions and see nothing but sky and sea did remind me how little I was.

When we arrived in Le Havre, I stood at the bow and looked down as they secured the massive ship and began unloading trunks and crates. Then, we were finally on land and in France. I was unsteady on my feet after all that time rocked by the rhythm of the sea. We took the two- or three-hour train ride to Paris. Mom's mother, Yvonne, and step-father, André, met us and fed us. My new grand-mère, Yvonne, noticed that my balance and coordination was worthy of French ridicule; she promptly dubbed me "Richard, Casse-pieds, Duc de Montparnasse." That translates into "broken feet" but often means "pain in the neck." None of this struck me as funny as a seven-year-old, it just hurt my feelings. The nickname stuck though, because I kept running into trees and tripping over curbs, providing ongoing evidence that casse-pieds pretty much fit. Once in a beauty salon on Les Champs-élysées, I tripped over a French poodle, fell forward and broke a solid glass ash tray with my face. Another classic casse-pieds moment for the evidence file.

It turned out that André and Yvonne owned an apartment building on rue Claude Bernard in the 5th arrondissement; eventually, we moved in there. It was a six-story walk-up with a communal lean-in type water closet they called a "Turkish Toilet." I think the French just like to blame stuff on the Turks. By the winter of 1951, I was eight and mom was four months pregnant with my sister Kim. Dad had spent the last 16 months painting like a madman: the natural bridge at étratat, street scenes of post-war Paris, portraits of street people and poets huddling for warmth over coffee at Le Dôme or Le Select in the heart of Montparnasse. This neighborhood and its cafés were made famous by painters, poets, dancers and hookers since the 1920's. Montparnasse had been a haunt for the likes of Josephine Baker, T.S. Eliot, Man Ray, Fitzgerald, Dali, Hemmingway and even Cole Porter. Dad had managed to extend our stay in France by taking commissions from the Saturday Evening Post; he'd ship an illustration back to NYC every couple of months. But with Kim on the way we'd be heading back to the States soon. By now I was doing the food shopping. It wasn't far to rue Mouffetard, the famous market street crowded with shops and stalls, vendors, fruit and vegetable carts, and the intoxicating aromas of baked goods mixed in with those of fish, chocolate and garlic; the air was heavy with it all. And everyone carried their groceries in little twine shopping "sacs." I was in the second grade at l`école communale and my French was improving. I was learning to negotiate with the merchants of rue Mouffetard. I could haul my “sac à provisions” up those six flights without much problem, and Mom could rest and prepare for our upcoming February voyage across the North Atlantic.

It turned out that André and Yvonne owned an apartment building on rue Claude Bernard in the 5th arrondissement; eventually, we moved in there. It was a six-story walk-up with a communal lean-in type water closet they called a "Turkish Toilet." I think the French just like to blame stuff on the Turks. By the winter of 1951, I was eight and mom was four months pregnant with my sister Kim. Dad had spent the last 16 months painting like a madman: the natural bridge at étratat, street scenes of post-war Paris, portraits of street people and poets huddling for warmth over coffee at Le Dôme or Le Select in the heart of Montparnasse. This neighborhood and its cafés were made famous by painters, poets, dancers and hookers since the 1920's. Montparnasse had been a haunt for the likes of Josephine Baker, T.S. Eliot, Man Ray, Fitzgerald, Dali, Hemmingway and even Cole Porter. Dad had managed to extend our stay in France by taking commissions from the Saturday Evening Post; he'd ship an illustration back to NYC every couple of months. But with Kim on the way we'd be heading back to the States soon. By now I was doing the food shopping. It wasn't far to rue Mouffetard, the famous market street crowded with shops and stalls, vendors, fruit and vegetable carts, and the intoxicating aromas of baked goods mixed in with those of fish, chocolate and garlic; the air was heavy with it all. And everyone carried their groceries in little twine shopping "sacs." I was in the second grade at l`école communale and my French was improving. I was learning to negotiate with the merchants of rue Mouffetard. I could haul my “sac à provisions” up those six flights without much problem, and Mom could rest and prepare for our upcoming February voyage across the North Atlantic.

Over the months, we had trekked through The Louvre, the galleries of Montparnasse and Montmartre and had even visited The Last Supper in Milan. The Mona Lisa was hanging in a dark, inhospitable corner of The Louvre in those days and was cordoned off from visitors only by a fat soft rope of the kind you might find in a movie house lobby. The Last Supper, too, I remember, seemed naked to the world. It was poorly lit and on a thin water-damaged 460- year-old wall. It survived WWII bombings and multiple attacks by vandals over the centuries. It all took a toll, scarring the magnificence of this masterpiece. When we were there in 1950, it was undergoing yet another round of restoration. Seeing it and the Mona Lisa during those years, the works seemed vulnerable and available, like they still, somehow, belonged to us. Revisiting the Mona Lisa in 1999, it no longer seemed of the people. Behind bullet proof glass, attended by guards and under such bright light, it seemed distant, like royalty or the Pope where the everyday citizen could only hope to be granted an audience.

Through our dozens of museum and gallery visits, Dad trained me to recognize the different styles. He'd hold his hand over the artist's name and make me guess who it was: Degas, Utrillo, Vlaminck, Lautrec, Cezanne. . .. I got good at it. We toured museums in Vienna, Rome, London. . . Dad always rushing up to cover the painter's name, testing my knowledge. I especially loved Paul Klee, Matisse and Modigliani, but my favorite was Miró.

I had been collecting coins and paper money since we'd been in Europe. My French family and friends of my parents would always contribute to my stash. One time, our butcher presented me with a string of centimes, the post-war kind with the hole in the center. This was before the government re-valued the franc and eliminated the centime. In those days though, the rate was about 300 francs to the dollar and, of course, 100 centimes to the franc, so a pound or two of centimes might be worth four or five cents. Nonetheless, over the months, I accumulated enough francs to buy a reproduction of one of Miró's playful fantasies painted on burlap. It was a wild under-seascape that drew me into another world, a world where an eight-year-old could lose himself. The magic of Miró is that he could locate his eight-year-old self and then present it in Technicolor. That framed print is still with me and still completely captivating.

A month before we sailed for New York, Dad managed to contact Mr. Miró and went to Barcelona to meet him. He made some wonderful photos of the man in his studio and told him the story of his boy saving up francs for the print. Even an artist of Miró's formidable reputation couldn't help being moved by a story like that and Miró clearly was. When Dad returned from Spain, he brought with him a first edition of the 1949 Editiones Colbato, "Joan Miró" by J.E. Cirlot with the following inscription, "pour mon jeune ami, Rick Smith, trés cordialement/Miró/I/1951."

Miró died on Christmas Day in 1983. His career spanned more than seven decades. His acclaim became, and remains, global. He appeals to all ages, not just eight-year-olds. His paintings, ceramics and sculptures reside in most of the world-class museums and collections. Some of his work, sadly, went down with the Twin Towers. It took some of the French Surrealist poets in Paris and the very welcoming climate of the United States in the late 1940's to jumpstart his phenomenal popularity. He was an outlaw and a dreamer, a rule breaker and a chance taker. He trusted simplicity and worked from a unique playbook. For a while, he was a Cubist. For a while he was a Surrealist. Even within those avant-garde movements, he was an iconoclast, an outrider consumed by his own dreamscapes. The isms just couldn't hold him. At the time he sent me his book, he was still, basically, an underground figure in his hometown. He had just returned from a triumphant visit to the U.S.A. I think America embraced him because he embodied the fresh and youthful energy of the sort discussed by De Tocqueville in his ground-breaking work, Democracy in America. I don't know where to file Miró's lifelong fascination with the floating disembodied foot. Sometimes I wonder if Dad told him about my nickname. Did that compel this Catalan Spaniard, this dreamer and image breaker, to inscribe a book to that American kid who walks into lampposts?